Every January, we collectively resolve that this will be the year we build our best habits—finally cutting out unprocessed food and committing to healthier eating to make up for the derailing and lawless indulgent period between Christmas and New Year’s.

Amongst my plans is to be mindful of my nutrition and like many others, I have subscribed to these goals instead of making peace with my foibles: to optimise the nutrients I’m feeding myself for optimum performance whilst on a calorie deficit. After all, what could a PhD student need more than a well-nourished brain? (A lot actually, but one must stay focused).

Neuronutrition is fascinating. A wide range of eating behaviors and nutrients have a complex multi-sided effect on self-regulation, metabolism, immune system, and brain function. Psychoneuroendocrinoimmunology (PNEI) has widened the role of nutrition, a tool with which the environment methodically shapes the metabolome and epigenome.

As an interdisciplinary field that ties together theories, practices, and research from neuroscience (including behavioral and social aspects), nutrition science (incorporating elements of nutrigenomics and precision nutrition), and neuropsychology. It allows for the focused study of various dietary components on the outcomes of behaviour and cognition and even the use of various nutrients to prevent and treat neurological disorders.

Diet, supplements, food additives, and the socio-environmental contexts of nutrition influence our behaviour, cognition, neurobiology, and neurochemistry. This relationship between nutrition and brain function is bi-directional—what we eat affects our brain, and in turn, our brain influences our dietary choices and food relationships.

Despite making up only 2% of total body weight, the brain consumes 20–25% of the body’s total energy expenditure. Even at rest, it remains highly active, regulating automatic functions like breathing, memory production, and heart rate. This constant activity demands fuel, and that fuel comes from our diet.

What the brain needs, the brain gets.

The human brain is 60% fat, with this fat playing a crucial role in structural integrity, neuron protection, and neurotransmission. Key omega fatty acids, like Omega-3 (DHA) and Omega-6, are essential for neural cell membranes. DHA, in particular, is concentrated in the brain’s gray matter and is critical for neuroplasticity, cognitive function, and memory—it even makes up 15% of the total fatty acid content in the human frontal cortex. Since the body doesn’t produce DHA on its own, we have to obtain it from our diet.

Beyond fatty acids, the brain relies on glucose from carbohydrates as its primary energy source. However, for those following a ketogenic diet, the brain shifts to using ketones produced by the liver as an alternative fuel. Additionally, nutrients like folate, copper, choline, and other micronutrients contribute to essential brain functions. However, an excess of certain nutrients, such as copper, can have adverse effects, potentially contributing to neurological disorders like Wilson’s disease.

Neuronutrition isn’t just about eating for brain health—it’s about understanding how the foods we consume shape our mental, emotional, and cognitive well-being. The brain functions best when it has a steady supply of nutrient-rich energy sources, stable blood sugar levels, and a sense of safety—meaning less chronic stress and fewer fight-or-flight responses, and more moments of calm, meditation, and balance.

Research has linked uncontrolled diabetes, cardiometabolic dysfunction, and malnutrition to increased health risks for the brain. Inadequate nutrient intake throughout the day can lead to deficiencies, impair cognitive function, and contribute to neurological issues.

The Antidepressant Food Rating was developed to identify foods with the highest nutrient density for preventing and treating depressive disorders. Among the highest-ranking foods were oysters, mussels, leafy greens, peppers, and cruciferous vegetables.

Beyond macronutrients, phytonutrients and bioactive compounds found in plants and herbs have demonstrated benefits for brain health. For example, flavonoids—abundant in purple, blue, and red produce—support cognition, while almost every color in nature offers the brain a unique advantage (so let’s ditch the beige plates).

We’ve also seen the rise of functional foods—products enhanced with probiotics, phytochemicals, and fiber at safe, beneficial levels. In Japan, researchers developed a beta-lactoline-based yogurt that improved memory, enhanced brain blood circulation, and increased concentration after six weeks of consumption.

Inflammation: the new buzzword

Neuroinflammation is increasingly recognised as a key player in brain ageing and neurodegenerative diseases. While environmental factors can contribute to this, highly processed diets rich in saturated and trans fats have been linked to low-grade inflammation and an increased risk of neurological disorders.

At a cellular level, neuroinflammation involves hyperactivation of peripheral and central glial cells, including Schwann cells, astrocytes, and microglia. These cells play a role in maintaining brain health, but when overstimulated, they can contribute to chronic inflammation and neurodegeneration.

I plan to write more about the Gut-Brain Axis soon as this has been a topic of major interest to me for the past five years or so. But briefly, our gut and brain are constantly communicating!! The wonderful Gut-Brain Axis! The gut is home to around 100 million neural and glial cells, forming the enteric nervous system, often called our "second brain."

If you’ve ever been hangry, stress-snacked, craved sweets when sad, or lost your appetite due to stress, you’ve experienced this gut-brain communication firsthand. Research into nutrition for trauma suggests that conditions like grief, depression, anxiety, autoimmune diseases, and ADHD can alter the size and function of specific brain regions. These changes can:

Increase nutrient and energy demands

Shift how we process emotions

Disrupt appetite signaling, pain networks, and sleep-wake cycles

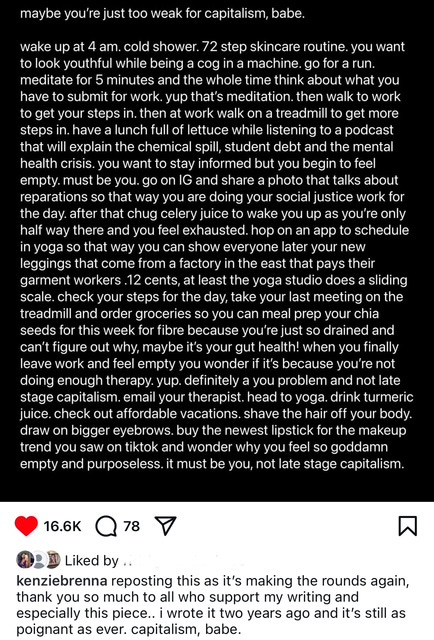

The price of wellness

You’ve probably seen the ads urging you to drink your greens, take ashwagandha, and sip on melatonin mocktails… health is wealth, after all. But in today’s economic climate, that wealth is looking increasingly expensive. So whilst I want to incorporate more mindful eating into my daily routine, as a student, it’s not so easy to overlook the price and “invest”.

Salmon-topped grain bowls, cottage cheese sourdough toast, biohacking routines, pilates sessions (seriously, like I know I’m here, but how are you at the studio at 10:30 AM—do you not have a 9–5?) - the modern wellness aesthetic has become somewhat of a status symbol.

This turns nutrition and wellness into an economic puzzle: Can we maximise what we can afford while avoiding the narrative that poor health is simply a personal failure? When healthy food and fitness becomes a privilege rather than a baseline, the conversation shifts from well-being to elitism and individualism.

I can think of countless times I’ve felt frustrated with my body, my health, and my relationship with food—only to completely overlook the role of nutrition. Amidst the daily stresses of life, the idea of following a strict, nutrient-dense (often expensive) diet can feel overwhelming. I think it’s also become somewhat of a joke online that if anything feels wrong with your body, yeah well, it must be your gut health.

I’m no clinician, but through epidemiological studies, there is some good news: you don’t need to be perfect. Studies suggest that even small, mindful changes—within your means—can support your brain and overall well-being. The key isn’t perfection; it’s simply paying attention to what your body needs and working with what’s accessible to you.

An interdisciplinary solution for an interdisciplinary field?

Another key question remains: How do we translate these insights into clinical practice?

From a public health perspective, I strongly advocate for nutritional literacy and acculturation. Within this, neuro-nutritional illiteracy represents a profound health injustice, deepening existing health inequities. If individuals lack access to nutrition education, practical skills, or culturally relevant dietary guidance, they are left vulnerable to poor health outcomes—further reinforcing systemic disparities.

Mindful eating – Developing earlier awareness of how food impacts mood, cognition, and overall well-being.

Culinary skill-building – Empowering individuals to prepare nutritious meals within their means.

Nutrition literacy – Ensuring accessible education on food choices, brain health, and disease prevention.

Integration of these elements and also holding those spreading misinformation accountable - making sure that that evidence-based guidance, rather than fad-driven narratives, shapes public understanding and policy.

With no pressure intended, a little brain food (and maybe a colourful plate) might just be the secret to thinking, feeling, and living a little better—one bite at a time. Why not give it a go?